UPDATE!

A longer more thorough analysis of this project, including an additional round of samples can be found under the “WORK” section of my website, or by CLICKING THIS LINK. :)

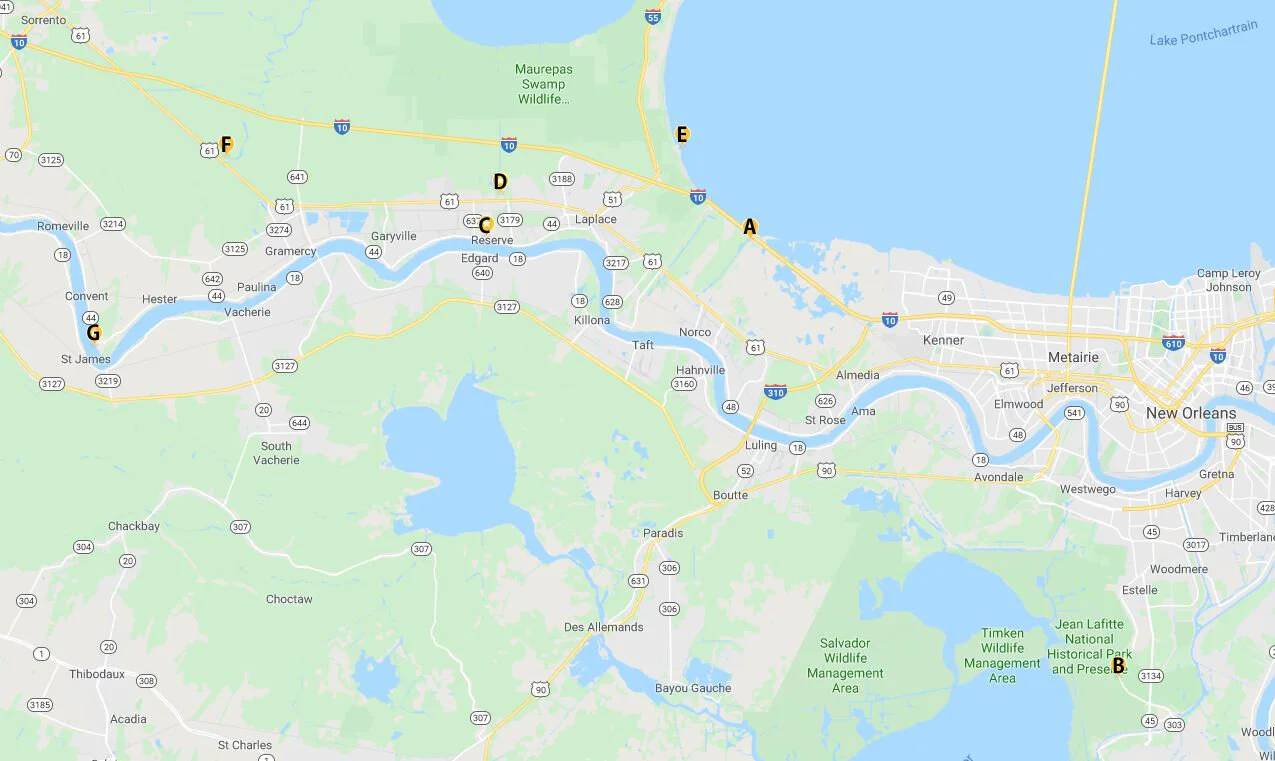

While in Louisiana last September, I collected water samples from a few rivers, a lake, a bayou and a swamp. Six of the seven samples were collected within the River Parishes, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, and one was collected just south of New Orleans. I believe it’s important to note that all samples were collected from the tops and edges of these bodies of water.

Collection Site Map

A. Bayou Trepagnier, near the Bonnet Carre Spillway, Norco, LA B. Swamp near Barataria Preserve, Marrero, LA

C. Mississippi River, Reserve, LA D. Reserve Relief Canal, Reserve, LA E. Lake Pontchartrain, Laplace, LA

F. Blind River, Gramercy LA G. Mississippi River, Convent, LA

There is a high concentration of petrochemical plants in Lousisiana’s River Parishes, also known as the chemical corridor, or Cancer Alley. Because of the dense population intermingled with chemical plants, residents are more greatly impacted by the high concentration of legal and sometimes illegal pollution. Some bodies of water, such as Blind River and the Mississippi River have advisories for the amount of seafood one should consume , if at all.

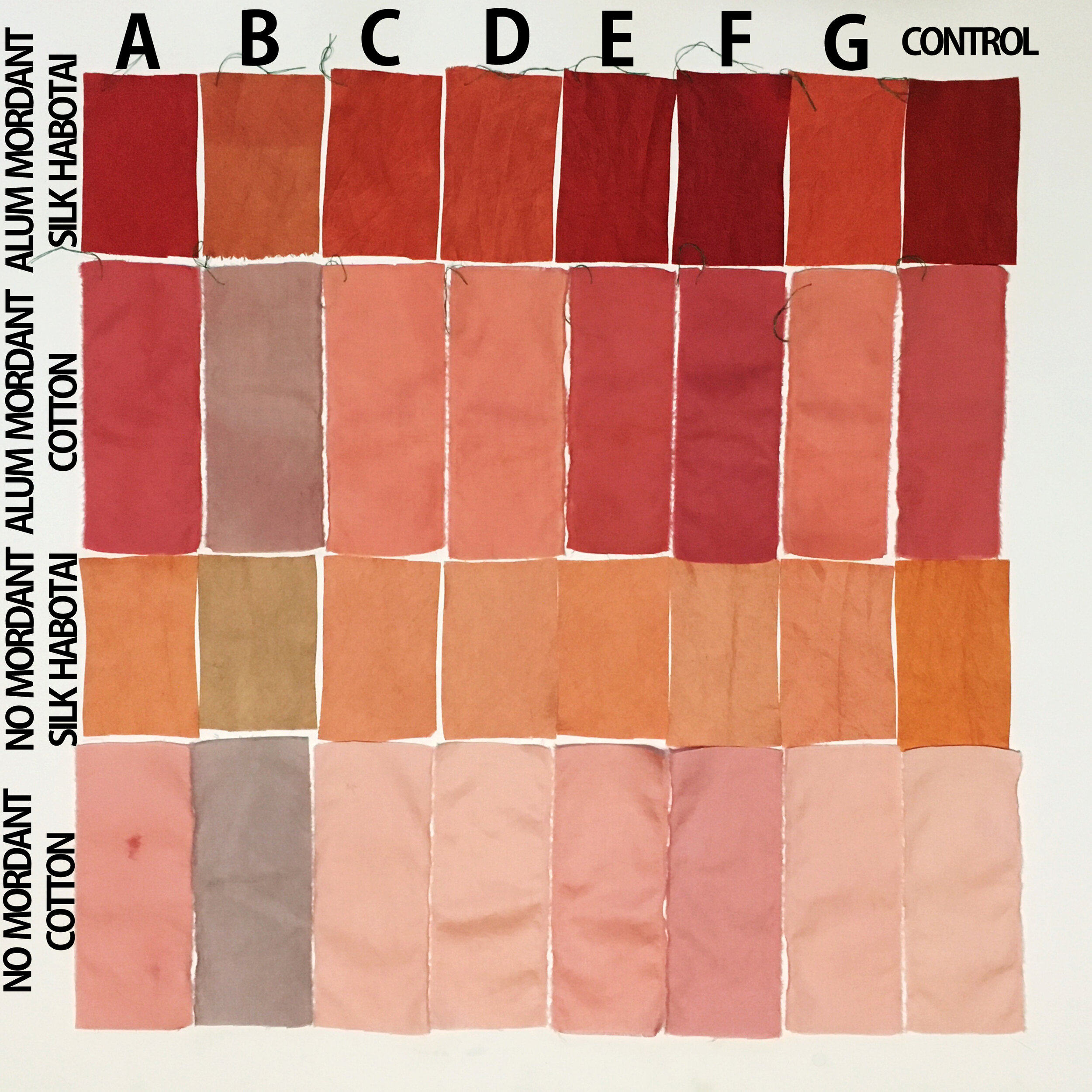

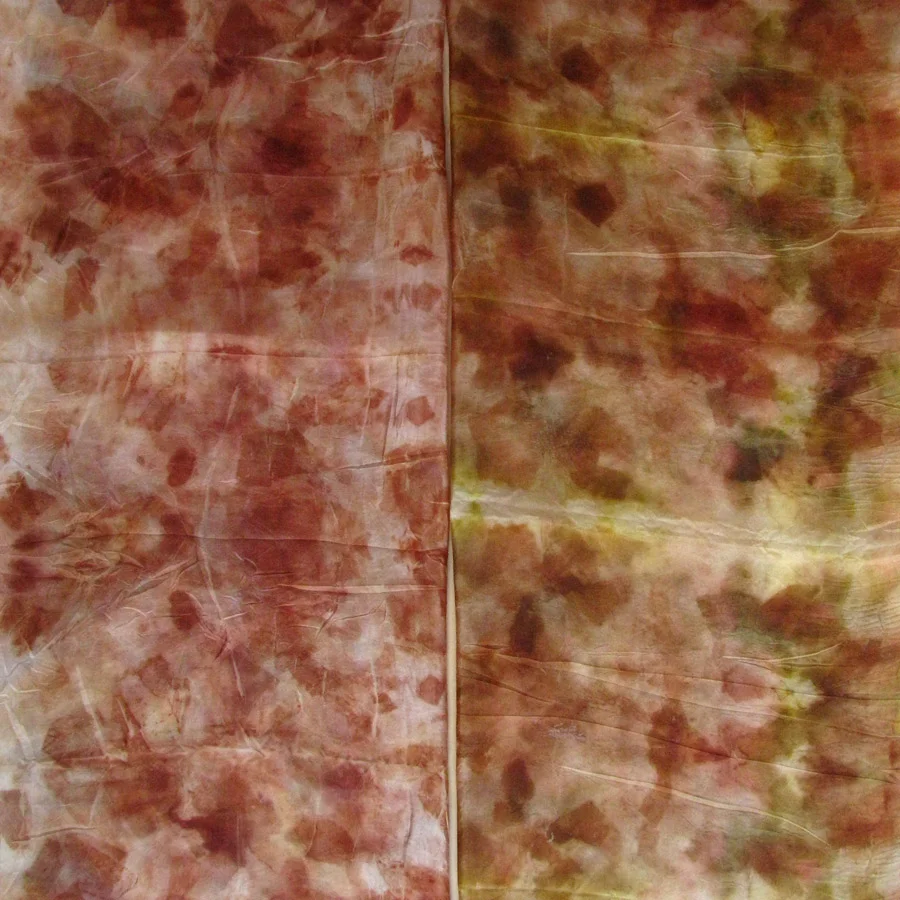

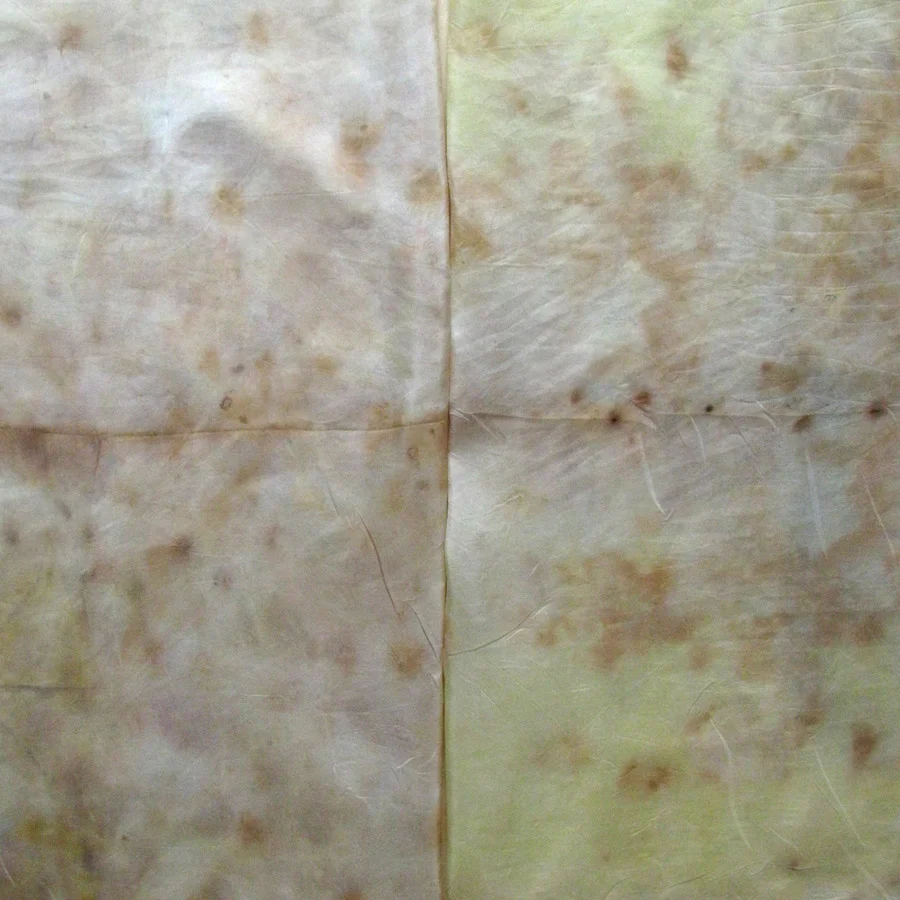

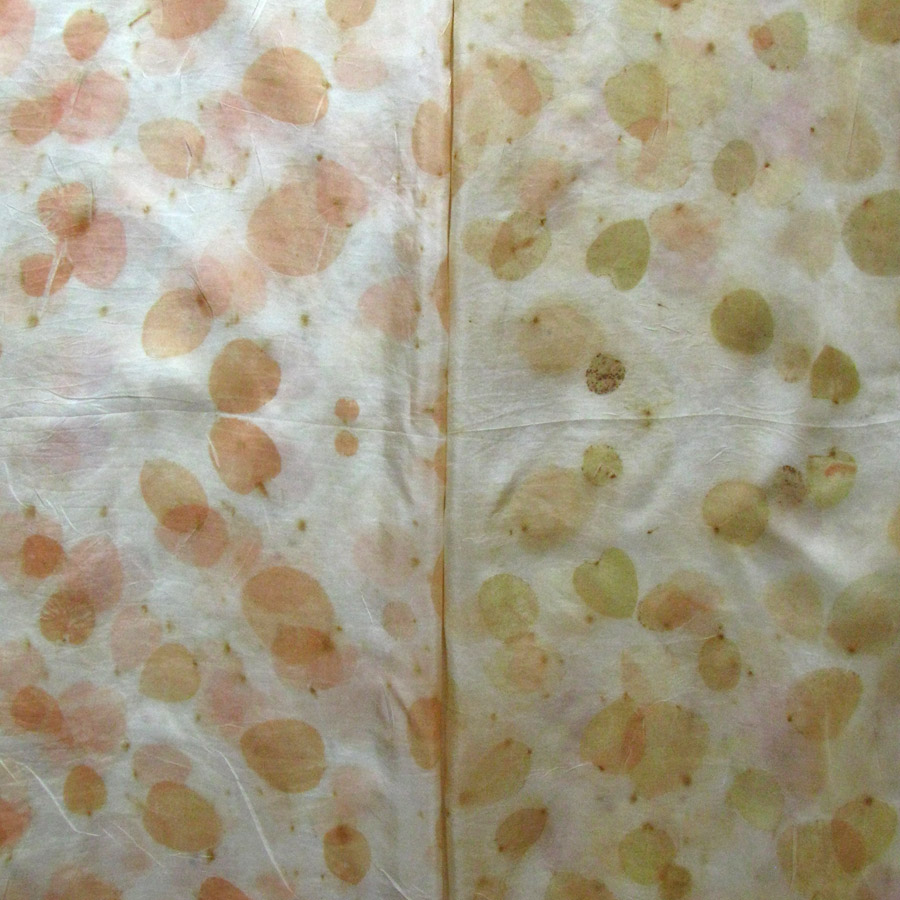

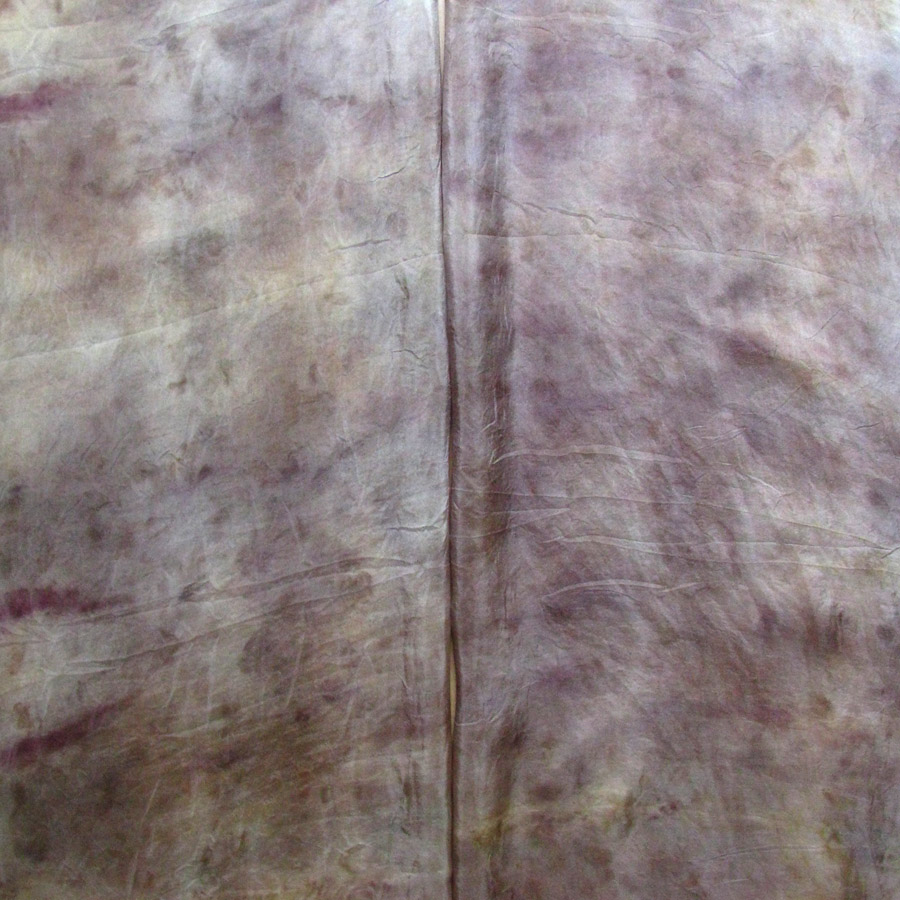

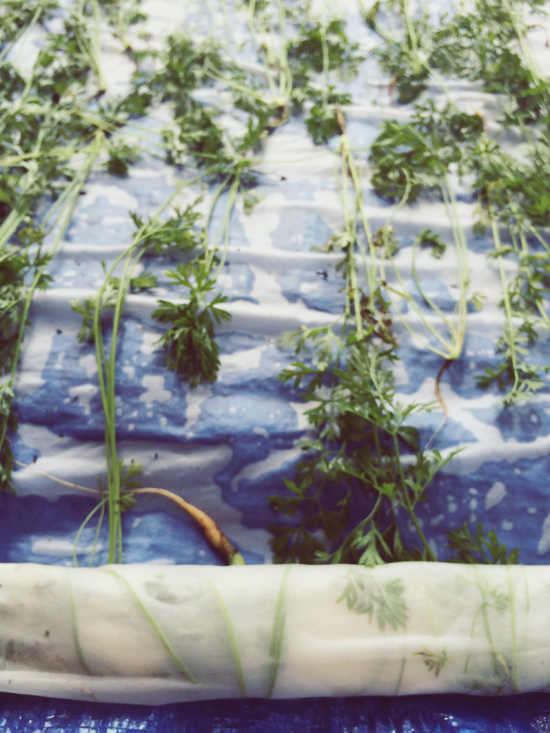

Because natural dyes are sensitive to water quality, I wanted to see if I would get varying results, using each water sample as a dye bath, dyeing 4 different fabric swatches in each bath. I included two swatches of silk habotai and two swatches of cotton, one of each was mordanted with alum, and the other left unmordanted.

A mordant is a metallic salt that is used to fix a dye in the fiber. When dyeing with most natural dye stuffs, a mordant is typically applied to the fabric first to increase light and wash fastness, it also affects the final color of the dye. “Historically, dyers often placed the mordant, dye, and fiber in the dye pot at the same time...Today, mordant is rarely put directly into the dye bath…[because] if mordant and dye are put into the dye pot together, they bind into an insoluble compound [lake pigment] before either one effectively penetrates into the textile.” -The Art and Science of Natural Dyes

I decided to use madder root (Rubia tinctorum) as my dye stuff. Madder root is a historic dye stuff and contains alizarin, which can produce a very pure red. But, depending on the water quality, dye technique and amount of dye stuff used, madder may also produce oranges, yellows, browns, pinks and purples.

Factors that shift/modify madder root: Alkaline solutions will achieve true reds. Acidic solutions will brighten and bring out more yellow. Iron shifts colors to purple and brown. Tannins will shift colors to more earthy tones.

Variables in water quality that may affect the outcome of a dye bath include pH levels, the presence of metal salts and other minerals, as well as other factors that I don’t fully understand…YET!

Before I added the madder root to each jar, I tested each water sample with water quality test strips. It provided information for 15 different variables. I only included the variables here that either differed across samples and/or were more than the lowest recorded levels/no trace.

The Experiment

Collected all water samples in mason jars 9/4-5/19

Tested water with test strips 12/28/19

Added ½ tablespoon of ground Rubia tinctorum to each jar

Created a control jar using distilled water

Scoured fabric samples in 1% WOF prosopol

Mordanted samples in 15% WOF alum

Started dye process 12/29/19- Placed water sample (now dye bath) and fabric samples in stainless steel pot, slowly rose temperature over 1 hour, careful not to boil, then rolling simmer for 10 minutes- Rinsed samples in tap water

Returned dye afterbath to jars

Strained jars of ground madder root dye stuff 1/3/19

Attempted to lake dye afterbaths (to see if there were any metal salts present) by adding ⅛ teaspoon of calcium carbonate to each jar, shake and let settle.** In jar A. I added ½ teaspoon (about 3g) soda ash - that brought the pH way too high - so I switched gears to calcium carbonate (thank you, Erika Molnar). Although, I have a feeling any metal salts presents in the water sample will have already either attached to the dye or fabric swatches.

The Results!

My Observations

Sample A. Bayou Trepagnier and E. Lake Pontchartrain are very similar, but are not exactly the same. Their similarity makes since because of their close proximity - Bayou Trepagnier and Lake Pontchartrain are also connected.

Sample B. Swamp near Barataria Preserve produced dull purples and browns. When I collected this water sample, the water was thick with duckweed. I tried to get as little duckweed in the jar as possible, but some slipped in. Instead of straining out the duckweed, I left it in the jar until right before I added the madder root, about three months later. I recently read that duckweed is a very effective bio-accumulator, often removing excess nutrients and toxic metals from the water. The water is dark because of the presence of iron. I don’t know if the soaking/somewhat decomposing duckweed released iron, creating a slight concentrate in the jar, or if the iron was just this present in the water where I collected the sample. Either way, the duckweed accumulated this iron from its source water. It is also possible that the soaking duckweed released tannin.

Samples from C. Mississippi River, Reserve, D. Reserve Canal and G. Mississippi, Convent were nearly identical to one another, but are lighter, duller and contain more yellow than the Control.

Sample F. Blind River produced the darkest and richest samples across the board.

Because the madder root was so finely ground, it was difficult to tell if any laking had occurred during the dye process. I did note that both Mississippi samples seemed lighter than the rest in their afterbaths with sediment at the bottom.

My Questions

What caused the unmordanted cotton Samples in A, B, E and F to hold more dye than the control?

What caused Samples B, C, D and G to be lighter in value overall? What caused the dye not to penetrate? Could these dye samples have contained metal salts, which bound to the dye, forming a lake, rather than binding to the fabric?

What caused Sample F to be overall darker (but still saturated) than all other samples? Could it be the presence of a mordant (metal salt) in the dye bath/water sample, which bound to the fabric, increasing its ability to absorb and hold dye? But, if that’s true, does it not disprove the possibility that the presence of metal salts resulted in the lighter samples?

Could it be, the difference in pH… Samples A, E and F were all slightly more acidic. This difference could have allowed the dye to penetrate the fabric, rather than immediately attaching to any metal salt present in the water sample, while Samples C, D and G were all slightly more basic, making it easier for the dye to attach to the any metal salts present in the water samples, rather than attaching to the fabric.

(Per Catharine Ellis’s recipe - when I make a print paste, I always add white vinegar before combining my mordant (metal salt) and dye liquid. Acid also works to split/break the bond between a dye and a mordant - aka split a lake pigment.)

Did I figure it out?!?

I would love input and analysis of my dye samples from any seasoned natural dyers, chemists, environmental scientists, etc.!

If my conclusions about the pH difference are true, then there must be some kinds of metal salts in the water that are not iron, copper or lead. I think it is possible for these bodies of water to contain metal salts naturally, but I don’t know for sure or what they would be? But also, all of these bodies of water are in very close proximity to many petrochemical and processing plants, who are all variously permitted by the LDEQ to release various amounts of chemicals into the air and store liquid waste in pits and ponds on their premises. Above are a few satellite maps showing my water sample collection sites from Cancer Alley with the various chemical plants, grain elevators, metal manufacturers, natural gas and nuclear energy plants and refineries circled in red.

Many of these plants provide the rest of the United States with a plethora of petrochemically derived food, clothes, cleaning products, furniture, pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, cosmetics, building materials, inks, bombs, fertilizers, pesticides, petrolium and single use plastics. Look around you, something near you was probably made possible because of at least one of the petrochemical plants in Cancer Alley. The residence of Cancer Alley have been in ongoing battles with Parish and State government officials about permitting new petrochemical plants to the area. Click this link to read about the fight against Formosa and consider supporting on the ground organizations like the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Rise St. James and Healthy Gulf. If you’re interested in learning more about Cancer Alley, I suggest picking up a copy of "Petrochemical America,” by Kate Orff and Richard Misrach.